Part III in the series “Romans: The Road Less Traveled.”

Romans 3:21-4:25

We continue our road trip through Romans today, and whenever I think of a road trip, the first thing that always comes to mind for me is, “What needs to be packed and how will we pack it?” I’m pretty sure that I have some mild form of obsessive-compulsive disorder that gets aggravated whenever it’s time to pack for a trip. There are weather reports to be consulted, itineraries to be evaluated, space considerations for both the suitcase and the car. Everything needs to be laid out, and I tend to drive my family crazy with my packing and repacking of the bags in order to get the optimal configuration for travel. And it’s not like I can figure this out once and remember it, make a list, etc. No, I go through the same frantic conundrum every time, trying to figure out how to organize all these different pieces and parts into a cohesive whole. I’m guessing many of you think about this in the same way. It would be great to have an organizing principle to help put it all together.

We continue our road trip through Romans today, and whenever I think of a road trip, the first thing that always comes to mind for me is, “What needs to be packed and how will we pack it?” I’m pretty sure that I have some mild form of obsessive-compulsive disorder that gets aggravated whenever it’s time to pack for a trip. There are weather reports to be consulted, itineraries to be evaluated, space considerations for both the suitcase and the car. Everything needs to be laid out, and I tend to drive my family crazy with my packing and repacking of the bags in order to get the optimal configuration for travel. And it’s not like I can figure this out once and remember it, make a list, etc. No, I go through the same frantic conundrum every time, trying to figure out how to organize all these different pieces and parts into a cohesive whole. I’m guessing many of you think about this in the same way. It would be great to have an organizing principle to help put it all together.

You know, I think the same thing is true when we look at Scripture, and particularly when we look at a text like Romans. Many of us learned to read the Bible as children, for example, and we remember the stories of Scripture as a bunch of disconnected stories laid out on the table, trying to make sense of them all. As we get older, we do the same thing with some of the theological concepts we read about in Scripture—faith, justification, grace, sin, etc. We know that we need all these things in order to be faithful Christians, but we’re not sure how they all fit together; how they can be organized in order to be useful on the journey of the Christian life.

You know, I think the same thing is true when we look at Scripture, and particularly when we look at a text like Romans. Many of us learned to read the Bible as children, for example, and we remember the stories of Scripture as a bunch of disconnected stories laid out on the table, trying to make sense of them all. As we get older, we do the same thing with some of the theological concepts we read about in Scripture—faith, justification, grace, sin, etc. We know that we need all these things in order to be faithful Christians, but we’re not sure how they all fit together; how they can be organized in order to be useful on the journey of the Christian life.

Sandra Richter, who teaches Old Testament at Wheaton College, calls this the “dysfunctional closet syndrome.” When we forget the organizing principle, we end up with a bunch of concepts and stories crammed into the suitcase, and when that happens (just like when taking a road trip), we can wind up leaving behind some essential things we need for the journey. When it comes to Scripture, Richter says, we need to first begin packing for the journey with a single organizing principle—the essential item of covenant.

In Romans 1 and 2, we looked at the problem we find ourselves in. Human sin exchanged the glory of God for a lie and sin is the disease that has plagued us all since the beginning. None of us is righteous, Paul reminded us, not even one of us. We have basis upon which to judge others because we’re as sinful as anyone else. We’re in a mess. The first 11 chapters of Genesis lay out the deep dysfunction of that mess. As Genesis 6 says of humanity, “Every inclination of their hearts was evil.” We can’t find our own way out.

But, as we said last week, while God “gives us over” to our sin, God never gives us up. Indeed, God’s way of dealing with the sin of the world is through covenant—the organizing principle of Scripture from Genesis 12 onward. Miss that and you’ll miss the message of Scripture in general and what Paul is saying in Romans in particular. Indeed, in the section of Romans we’re looking at today, Paul is taking us back to Genesis to remind us of this organizing principle of covenant. It’s important that we start there to get one of the main things we need to pack and take along on the Romans road.

So, what is “covenant?” Today we mostly use that word in our homeowners associations to describe the stuff we’re supposed to do and not do with our properties. In the ancient world, however, “covenant” expressed the relationship between two parties, most often between a patron and a client. The patron (usually a wealthy and powerful individual) would offer protection and security to a client (a lesser person) in exchange for the faithfulness and fidelity of the client. The client would be required to do what the patron asked and if the client went against the patron there would be trouble.

Think of it kind of like Marlon Brando, Don Corleone in the Godfather. At the beginning of the movie, a man comes to Don Corleone with a problem, asking for justice against the people who harmed his daughter. Here’s the clip:

That’s the patron-client relationship. I will do this for you, but you will be loyal and come when I call.

Humanity had a problem in Genesis 1-11, but they don’t come to God with it. Instead, in an amazing reversal, God comes to them. In Genesis 12, God, the patron and creator of the world, chooses to address the human problem of sin. And they way he does it is by making a covenant with one of those humans—a man named Abraham. Look at Genesis 12:1-3 – “Now the Lord said to Abram, ‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.” The God and Father makes a promise, and in one of the most succinct yet important verses in the whole Bible, Genesis 12:4, we learn what Abram did in response: “So Abram went as the Lord had told him.” Abraham is the first traveler on the road that leads us to Romans and God’s redemptive plan for the world.

This is an essential understanding that we need to pack as we journey on the Romans road. The story of Israel, Abraham’s family, is the foundational story of how God is going to rescue the world from sin and death, and God’s covenant with Abraham is the mission statement for this mission of God.

Of course, as Scripture reveals to us, Abraham’s family isn’t exactly a faithful client. The people through whom God was going to save the world are themselves in need of saving. God liberates them from slavery in Egypt and they respond by turning away from him to idols. God grants them the land promised to Abraham, but they misuse and it and fill it with tributes to gods made of wood and stone. The people who were to be part of the solution were going to also be part of the problem. If God was going to keep the rescue on track, he would have to deal with the problem in a different way and even here in Genesis, at the beginning of the story, we see God working that out.

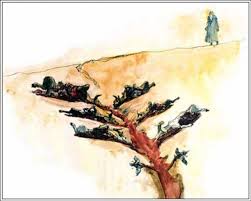

In the ancient world, making or “cutting” a covenant required a particular ceremony which involved taking an animal and cutting it in two, laying the two parts on two sides. At that point, then, the client would walk through the bloody pieces as a way of saying, “May what has happened to this animal happen to me if I break the covenant.” It was to be a graphic reminder that the client’s failure to uphold the covenant would have dire consequences.

In Genesis 15:7, Abram asks for a sign that all that God has promised is actually going to happen. So God tells him to go get several animals: a heifer, a goat, a ram, a dove, and a pigeon, and cut them in half (except for the birds). An ancient reader would know what this meant: Abram was going to have to walk through this bloody mess as a demonstration of his promise to keep God’s covenant, or else.

But when the ceremony actually takes place in verse 17, we see something very unusual. It’s not Abram who walks through the bloody pieces, it’s God in the form of a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch that makes the trek through the mess. Instead of marking Abram’s promise to keep the covenant, God—the patron—now also takes on the client’s role and promises, under the pain of his own blood and death, to keep the promise to Abram and is family and deal with human sin once and for all. The God Father will be faithful even when his people are not.

And this, Paul says in 3:21, is all fulfilled in Jesus. The righteousness of God, the covenant faithfulness of God, has been revealed, attested by the law and the prophets—the whole witness of the biblical story—the righteousness of God revealed through the faithfulness of Christ. That distinction in 3:22 is important. I mentioned this briefly last week. In many English translations (including the NRSV) it says “the righteousness of God through faith in Christ” but the context and the Greek are better rendered as the righteousness of God though the faithfulness of Christ for all who believe.

This is a key to Paul’s understanding of Jesus. So often, Christian theology has detached Jesus from the story of Israel, as though he dropped out of nowhere and nullified all those silly stories and laws from the Old Testament. Notice, for example, that in many churches you will rarely hear preaching from the Old Testament unless it’s to use a story as a moral example, and the fact that when people want to evangelize others they only give them the New Testament. I joked with my Disciple class saying that some of them just endured the first 17 weeks of studying the Old Testament just so that they can get to the “good stuff” of the New. But understanding covenant as the organizing principle of BOTH testaments is essential if we are to understand Jesus and what Paul is trying to tell us.

Paul, along with the other New Testament writers, sees Jesus as Israel’s long-awaited Messiah, the one who was to be the faithful Israelite, doing for Israel what she could not do for herself. Jesus comes from Abraham’s family, but where Abraham’s family failed to live up to the covenant with God, Jesus, Israel’s long-awaited king and representative, had done so. He is obedient to God, even to the point of death as Paul will say in Philippians 2. He fulfills Israel’s mission—a light to the world that draws all people. And in representing Israel, then, Jesus represents the world. He is humanity renewed, as Paul will tell us in Romans 5, and he has demonstrated what it means to be God’s covenant people in his life, death, and resurrection from the dead. The plan for God to put the world right at the last had been realized in the middle of history, within the covenant-fulfilling work of Jesus, dealing with sin and its resulting death through his own death, launching the beginning of God’s new creation with his resurrection, and sending forth his Spirit to enable humans, through repentance and faith, to become the people of that coming new creation—not just someday, but right now, in the present.

Look at how Paul says it in 3:24, “they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.” In Christ, God walks again through the bloody pieces of the covenant broken by human sin and takes the due punishment on himself. The covenant faithfulness of God, climaxing in the covenant faithfulness of Christ, puts everything right, including those who put their faith in him. As Paul says in 3:26, God did all this “to prove at the present time that he himself is righteous and that he justifies the one who has faith in Jesus.”

Now we need a little detour here to discuss what Paul means by “justification by faith.” This is one of the central doctrines of the Protestant Reformation, of which we are all theological descendants. “Justification by faith” has been used in a lot of ways throughout Christian history, most of them (at least in our time) about how one can get to heaven in the future. But when you look at Paul’s use of the term, it’s really more about the present. Indeed, for Paul, “justification” is focused on who is part of God’s people right now. God’s grace, God’s answer for the human problem of sin, has come into the world through the covenant faithfulness of Christ, and when we respond to that grace with faith, we are justified, “put in the right” by that faithfulness and we become part of God’s new community

In 3:27-31, Paul declares that justification by faith, not ethnicity or rituals of the law, is the primary identifying marks of Jesus’ community. This is a key theme in many of Paul’s letters, especially in Galatians and here in Romans. Keep in mind that when Paul refers to the “law” here he’s talking primarily about the laws of Moses that were given to mark out Israel from their pagan neighbors—mainly, three things: circumcision, Sabbath-keeping, and the kosher purity laws (food laws and the like). Paul says to those few Jewish Christians in Rome, “Hey, you think you can boast because you’ve been keeping kosher? No, that’s not what marks you as part of the community of Christ. Indeed, Paul says in 3:28, it’s faith that marks us, not the works of the law. Otherwise, God is only interested in the Jews who follow them. No, the Gentiles are part of this community, too. It doesn’t matter if you’re circumcised or you’re uncircumcised, Paul says in 3:30—what matters is that you have faith. Faith in Christ is the primary mark of those who are part of God’s put right and right-putting people.

That’s why Paul takes the Roman church back to Abraham. Abraham was around before there ever was such a thing as circumcision, or Sabbath-keeping, or food laws. So what was the essential item Abraham needed in order to be the father of many nations, to be the first of a community of God’s people that now includes even us? Faith. Paul quotes Genesis 15–“Abraham believed God and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.”

Abraham went as the Lord told him. Abraham looked up at the stars and though he knew it was physically impossible for a man “as good as dead” to be the father of many nations, he believed God anyway. Abraham stood by and watched God walk through the bloody runway, and knew that God would keep his promises, no matter what it cost. And because of that faith, God credited Abraham with righteousness, the standing of one who is “in the right” with God. Abraham thus became the “ancestor of all who believe without being circumcised who thus have righteousness reckoned to them, and likewise ancestor of the circumcised…” (4:11-12).

If covenant is the organizing principle for the Christian journey, faith is the first thing we need to put in our kit bag. Now, lots of people think of faith in different ways. For many people, who live in the Greek-inspired Western world that is all about mind and body dualism (separating body from spirit, thoughts from actions), “faith” is simply an intellectual assent to a set of principles about God, or about Jesus. Belief is what you “think,” therefore if my thoughts are right, then I am right. It doesn’t matter that much what I do, so long as I believe correctly. This is the reason why in the US, a thoroughly Epicurean culture that ancient Greece would have been proud of, 74% of Americans say that they believe in God, but less than 25% attend worship in a community of faith at least 2-3 times per month. Not that being in church makes you a Christian anymore than being circumcised did in Paul’s day (who would sign up for that?). But the point is that many people like the idea of faith, just not the practice of it. As G.K Chesterton once put, “Christianity has not been tried and found wanting, it has been found difficult and not tried.”

If covenant is the organizing principle for the Christian journey, faith is the first thing we need to put in our kit bag. Now, lots of people think of faith in different ways. For many people, who live in the Greek-inspired Western world that is all about mind and body dualism (separating body from spirit, thoughts from actions), “faith” is simply an intellectual assent to a set of principles about God, or about Jesus. Belief is what you “think,” therefore if my thoughts are right, then I am right. It doesn’t matter that much what I do, so long as I believe correctly. This is the reason why in the US, a thoroughly Epicurean culture that ancient Greece would have been proud of, 74% of Americans say that they believe in God, but less than 25% attend worship in a community of faith at least 2-3 times per month. Not that being in church makes you a Christian anymore than being circumcised did in Paul’s day (who would sign up for that?). But the point is that many people like the idea of faith, just not the practice of it. As G.K Chesterton once put, “Christianity has not been tried and found wanting, it has been found difficult and not tried.”

But the biblical definition of faith requires something more. Abraham, for example, didn’t simply say, “OK, God, I believe you.” Abraham went. He packed up his family, his belongings, and traveled to a place he’d never seen before. He trusted that God would bless him with a family, even when it didn’t seem possible. He looked up at the stars and ordered his life around the promise of God, believing that God would do what he promised.

This is the sort of faith that really trusts God. Hebrews 11 lists person after person in Scripture who reordered their lives “by faith” in God. When Jesus called his disciples, he didn’t say to them, “Hey, believe in me,” or “think about me” or “agree with these four points about me.” No, Jesus said, “Follow me.” The disciples would reorder their whole lives around Jesus. Those who would not were left behind. God isn’t calling us to simply be a collection of people who intellectually agree with principles about Jesus. He is calling us to be a community of people who are put right and are right-putting by ordering our lives around him and his promises. It’s this sort of faith that Paul says will be “reckoned to us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead, who was handed over to death for our trespasses and was raised for our justification” (4:24-25). The results of that justification by faith and how we begin to live out that faith will be our topic next week as we continue with chapters 5-8.

In the meantime, I invite you to think about your own faith. What does it mean to you? Is your faith in Christ or is it faith about Christ? Does your faith in Christ alter how you live your life? Your priorities? Your relationships? Does your faith determine what you spend your time, your money, your attention on? Does your faith take you, like Abraham, to places you would have never thought to go on your own, or is it familiar and predictable? Oh yes, faith about Christ is fairly easy, requiring only getting your thoughts right. Faith in Christ, however, requires a recalibration of our whole lives toward his promises. It’s the difference between faith and faithfulness—one is about thinking about it, the other is about living it out. It’s the latter that marks us the people God called us to be.

So, pack wisely, my friends. The way of faith is a long road. Indeed, Jesus himself said it would be a cross-bearing road. But it’s the road to God’s future—a future we can begin living, working, and walking in today. Amen.