The life of Barabbas raises the question: “What am I zealous for?”

Matthew 27:15-26

If you were a pilgrim in Jerusalem during the Passover in the spring of 29AD, one of the questions that you might have heard on the lips of people as you walked around the marketplace or in the courts of the Temple would have been a question that Jews had been asking for quite some time: “How and when will the kingdom of God come?” It was a question that would have been especially relevant during the festival as people gathered from around the Mediterranean world to worship at the temple and celebrate the meal that commemorated the liberation of the Jews from slavery in Egypt under Moses—a question about when God’s final liberation would come.

If you were a pilgrim in Jerusalem during the Passover in the spring of 29AD, one of the questions that you might have heard on the lips of people as you walked around the marketplace or in the courts of the Temple would have been a question that Jews had been asking for quite some time: “How and when will the kingdom of God come?” It was a question that would have been especially relevant during the festival as people gathered from around the Mediterranean world to worship at the temple and celebrate the meal that commemorated the liberation of the Jews from slavery in Egypt under Moses—a question about when God’s final liberation would come.

After all, those who gathered in the city knew that they were not truly free—at least not yet. The Romans had come in 63BC under Pompey and took over the city, the latest in a parade of conquering empires that had dominated or at least threatened to dominate Israel for nearly 600 years. In various ways, Jews were wondering if this was the year when the Messiah would finally come and save them and set them free for good.

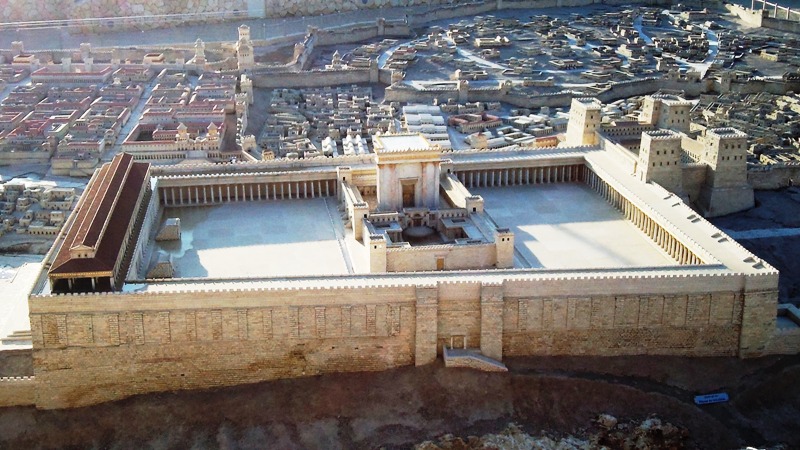

All of that was bound up in the phrase “kingdom of God.” Many modern Christians assume that “kingdom of God” or “kingdom of heaven” (the two are used interchangeably in the Gospels) means a heavenly kingdom somewhere far away, but if you were a first century Jew the meaning was a lot more immediate. For them, “kingdom of God” meant the reign and rule of God on the earth—the fulfillment of the promises of God to dwell with his people and rule them directly. The temple that dominated the Jerusalem landscape was the downpayment on that promise, the second temple on the site of Solomon’s first, where God once dwelt in glory and would again one day. The Messiah, many believed, would be the one who would pave the way for God’s glory to return and make Israel an independent and holy nation once again with God himself in the seat of power.

But while most Jews believed in the promise of the kingdom, they did not agree on how it would finally come about. It’s difficult historically to talk monolithically about “the Jews” when, in fact, there were many different sects of Jews that had different ideas on how the kingdom of God would arrive. We read about some of these sects in the New Testament—names that are familiar to its readers. The Pharisees, for example, were a conservative sect that believed that God’s kingdom would come only when the people all obeyed the law of Moses perfectly. Purity, for them, was the most important criteria for the kingdom. The Sadducees, on the other hand, represented the wealthy class who’s beliefs were not that interested in getting worked up over the kingdom of God. They, after all, had it made because of their collusion with the Romans. The Essenes left behind Jerusalem all together, believing that they were the pure ones through whom God’s kingdom would finally come on earth. They moved out in the desert and started writing and copying Scriptures, living a monastic life and giving us what are now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. For them, as for the Pharisees, purity and strict adherence was the key to the kingdom.

But while most Jews believed in the promise of the kingdom, they did not agree on how it would finally come about. It’s difficult historically to talk monolithically about “the Jews” when, in fact, there were many different sects of Jews that had different ideas on how the kingdom of God would arrive. We read about some of these sects in the New Testament—names that are familiar to its readers. The Pharisees, for example, were a conservative sect that believed that God’s kingdom would come only when the people all obeyed the law of Moses perfectly. Purity, for them, was the most important criteria for the kingdom. The Sadducees, on the other hand, represented the wealthy class who’s beliefs were not that interested in getting worked up over the kingdom of God. They, after all, had it made because of their collusion with the Romans. The Essenes left behind Jerusalem all together, believing that they were the pure ones through whom God’s kingdom would finally come on earth. They moved out in the desert and started writing and copying Scriptures, living a monastic life and giving us what are now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. For them, as for the Pharisees, purity and strict adherence was the key to the kingdom.

But then there were the zealots, named for their “zeal” for the kingdom of God. They believed, however, that the kingdom of God would come only when the Gentile pagan invaders were expelled from the city and land and that had to be done even if it meant the shedding of blood—the blood of the Romans and their collaborators and their own blood—in a violent revolution.

But then there were the zealots, named for their “zeal” for the kingdom of God. They believed, however, that the kingdom of God would come only when the Gentile pagan invaders were expelled from the city and land and that had to be done even if it meant the shedding of blood—the blood of the Romans and their collaborators and their own blood—in a violent revolution.

The zealots took their cues from an earlier period in Israel’s history about 140 years before. That was when the Maccabee family picked up swords and expelled another foreign invader, the Seleucids under Antiochus Epiphanes. We talked about them a little last week, the ones who sacrificed pigs on the altar of the temple—a “desolating sacrilege” in the eyes of pious Jews. The Maccabees mounted a guerrilla war against the invaders and drove them out, purified the temple, and ushered in about 100 years of Jewish self-rule. The zealots in Jesus’ day certainly would have had this in mind as they went about their own business of terrorizing Roman interests.

Interestingly, some of these zealots were among Jesus’ disciples. “Simon the Zealot” was certainly one, but there may have been others. Some scholars believe Judas may have been among them and that even Peter may have had zealot leanings. Some estimate that fully half of Jesus’ disciples thought of themselves as revolutionaries, which puts a lot of their conversations about greatness and carrying swords in perspective.

Which leads us to the story of another zealot, the notorious criminal named Barabbas. Luke tells us in his version of the story that Barabbas had committed “insurrection and murder,” which places him squarely in the zealot camp. The Greek word for these zealous revolutionaries was “lestai”—a word that gets translated variously in English New Testaments as “bandit, thief” or “robber.” More about that later, but the point is that Barabbas is no common criminal—he is a rebel, a terrorist or a freedom fighter, depending on whose side you were on.

Barabbas’ name means, in Hebrew, “son of the father.” That’s an interesting name since most proper names actually named the father, like Simon bar Jonah (Simon, son of Jonah). Even more interesting is the fact that many of the early manuscripts call him “Jesus Barabbas.” Jesus was a common name in Israel (a form of “Joshua,” another freedom fighter), but the juxtaposition of two Jesus’ in the Gospels is most certainly not a coincidence. We know who Jesus of Nazareth’s real father was, but we don’t know who fathered Barabbas. Some scholars speculate that the Gospel writers were implying that he was actually a son of the devil because of his acts. At any rate, Barabbas’ vision of the kingdom of God was one that involved working at the point of a sword. Indeed, the revolutionary slogan of the zealots was “no king but God,” and if Jesus Barabbas had heard of Jesus of Nazareth, he would have heard his preaching on the kingdom of God as good news. If God’s kingdom was coming, Barabbas may have thought, then the real revolution is here. It’s clear that some of Jesus’ disciples may have been thinking the same way. Otherwise, why would they be carrying around swords when Jesus was arrested?

Jesus of Nazareth had told his disciples to put their swords away, however. He preached about the kingdom of God as not coming with force but with a subversive movement of grace—like a mustard seed, or a little leaven in the dough. He taught love of enemies, turning the other cheek when struck, walking the extra mile. In the Roman world, a soldier could grab a civilian and force him to carry the soldier’s pack for one mile. Jesus said, if they make you carry it one mile, volunteer to carry it two. Jesus also talked about picking up a cross, which the zealots would have heard as a call to fight to the death, even if it meant capture and the penalty for insurrection, which was always a horrible death on a cross. Jesus, however, meant it as a symbol for non-violent suffering.

Most importantly, Jesus attacks the central symbol for the zealots, which was the temple. It’s instructive that when the later Jewish revolts took place, the zealots struck coins on them with images of the temple. For them, the temple was the symbol of Israelite freedom—a religious place turned into a receptacle of all their revolutionary dreams of self-rule. At the beginning of that week in Jerusalem, Jesus had gone into the temple and upset the tables of the money changers, driving them out. But look at what he says as he does it: “My father’s house is a house of prayer but you have made it a den of….lestai!” It wasn’t merely a comment on economic corruption—after all, the money had to be changed from Roman to Jewish coin to avoid violating the second commandment—it was instead a comment on the futility of revolution and the proclamation of God’s judgment on it and its symbol the temple.

Most importantly, Jesus attacks the central symbol for the zealots, which was the temple. It’s instructive that when the later Jewish revolts took place, the zealots struck coins on them with images of the temple. For them, the temple was the symbol of Israelite freedom—a religious place turned into a receptacle of all their revolutionary dreams of self-rule. At the beginning of that week in Jerusalem, Jesus had gone into the temple and upset the tables of the money changers, driving them out. But look at what he says as he does it: “My father’s house is a house of prayer but you have made it a den of….lestai!” It wasn’t merely a comment on economic corruption—after all, the money had to be changed from Roman to Jewish coin to avoid violating the second commandment—it was instead a comment on the futility of revolution and the proclamation of God’s judgment on it and its symbol the temple.

In short, Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God, didn’t fulfill the visions of the zealots. His revolutionary-minded disciples were no doubt confused by this all the way through their time with him—a revolution with no swords? Some of his hangers on began to leave him at this point. In fact, some scholars suggest that one of the reasons Judas betrayed Jesus was out of his disappointment that the revolution hadn’t begun. Maybe by getting him arrested it would cause an uprising. But it didn’t and Judas was left alone holding the bag.

If Barabbas had ever encountered Jesus before that day in the Praetorium, he might have seen him as weak and ineffective, just another holy man without a real plan. And yet there is Jesus on trial, accused of doing the very thing of which Barabbas himself was absolutely, unapologetically guilty. Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God, had done nothing under Roman law to deserve a cross, while Jesus Barabbas deserved nothing less.

And yet these two Jesus’ do have something in common. Both men seemed to believe that their deaths would mean something. Jesus Barabbas believed that his death would somehow advance the cause against Rome, a cause worth killing and dying for, and he would go to his cross knowing that he had taken some of the infidels with him. As he awaited his death sentence, a foregone conclusion, he might have imagined that from his cross he would look at the temple in the distance and pray that others would pick up his example and die for their country as well.

And yet these two Jesus’ do have something in common. Both men seemed to believe that their deaths would mean something. Jesus Barabbas believed that his death would somehow advance the cause against Rome, a cause worth killing and dying for, and he would go to his cross knowing that he had taken some of the infidels with him. As he awaited his death sentence, a foregone conclusion, he might have imagined that from his cross he would look at the temple in the distance and pray that others would pick up his example and die for their country as well.

Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God, however, had a very different vision of his own death—he was dying for the whole world. He would not kill for that vision, but he would die for it and take as many people as possible, both Jews and Gentiles, with him from death to life. When you put it in that perspective you could argue that Jesus Barabbas, son of the father, was selling his life too cheaply—his vision immediate, temporary, and political. Jesus, Son of God, however, was selling his life for the world.

When Pontius Pilate stood on the steps of the Praetorium and offered the crowd the choice between Jesus Barabbas and Jesus of Nazareth, it’s inevitable which one they will choose. Their vision is too limited to choose otherwise. They are looking for the quick fix, for visible results. Barabbas and his compatriots can offer that. Jesus of Nazareth, however, had taught that the quick fix was the destructive one. In Matthew 24, he warns of the coming destruction on the temple and Jerusalem that will most certainly occur if the zealots get their way. “When you see the desolating sacrilege in the temple, as Daniel spoke about (referring again to the revolt of the Maccabees), then those in Judea must flee to the mountains. Go back to your house, grab your stuff, and get out because the zealots will ultimately get the war that they want and it will be the end of everything you hold dear.” That’s the gist of Matthew 24:15-18.

But that was still in the future. Right now, the crowd will choose the one who they want and leave the innocent one to die, hung on a cross between two others who are “lestai” themselves. Barabbas’ revolution would continue. Jesus’ revolution would seemingly end, though we know it was just beginning.

Most of the sermons I’ve read or heard on Barabbas point out that it’s a story that’s a microcosm of the Gospel. We are like Barabbas, absolutely guilty of our sins, and yet Jesus the innocent one dies in our place. Barabbas was the first person in history who could say very literally that Jesus died for his sins, and in doing so he died in the place of all us sinners as well. That’s certainly a good angle to take for this story.

But there’s another question that the story of Barabbas raises for me and it’s the question, “What am I zealous for? What vision of the future, the kingdom of God, would I be willing to give my life for?

History is full of movements like Barabbas’—violent revolutions designed to bring in a particular vision of the future through killing and dying. Barabbas might have felt at home among any number of these movements. He could as easily been a member of ISIS as he could have been dropping the guillotine in France in 1789, or shelling Fort Sumter in 1861, or tarring and feathering Tories in 1775. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist. It’s all a matter of perspective.

But while it’s easy to identify zealotry that is willing to kill and die for a cause, no matter how evil or even how seemingly just, there are more subtle kinds of zealotry for which people will sell their lives.

Even if they never pick up a sword like Barabbas or run off to war, there are plenty of people in our own culture who are zealous and, yes, are willing to die for inadequate visions of the kingdom: money, success, status, sex, power, revenge, just to name a few (come to think of it, people will kill for those as well). The proof is everywhere: we have the highest rates of heart disease, obesity, and injury in the world. We work longer hours, we sacrifice our families, all in the name of pursuing our vision of the good life, which turns out not to be good for us at all. Like the crowd standing outside Pilate’s judgment seat, we sell can our lives for cheap and clamor for the quick fix, the vision of a future that is fleeting, temporary, and prone to destruction.

But there’s a different sort of zealotry that’s actually worth giving our lives for—the zealotry of Jesus Christ. It’ a political zealotry for sure, but its politics are part of a real, lasting, eternal vision.

Jesus offers us the vision of a kingdom that does not require killing for, but that is certainly worth dying for. He is ironically crucified as a revolutionary between two revolutionaries, and yet his revolution is one built on the power of love, not violence. In the midst of his pain as he hangs on the cross, unjustly accused, sentenced, and condemned to death, he does not cry out curses and abuse on his tormentors, as do the dying “lestai.” Instead, he forgives them. He dies with love on his lips, not hate. He didn’t sell his life for cheap, but spent his life expensively, extravagantly, for the benefit of the world. His death advances an eternal cause—it is death that leads to life. He called disciples who would share that life, that vision with him, even if it led them to their own cross. They would not die seeing the end of hope, but as Jesus’ resurrection from the dead proved—it was only the beginning of God’s kingdom. He’s still calling us to follow him in the way of the cross. He died in our place so that we might live—not so that we can throw away our lives on cheap, imitation, warped visions of the future, but to spend them wisely, extravagantly, on his very own mission and vision of a world free from sin and death.

Jesus offers us the vision of a kingdom that does not require killing for, but that is certainly worth dying for. He is ironically crucified as a revolutionary between two revolutionaries, and yet his revolution is one built on the power of love, not violence. In the midst of his pain as he hangs on the cross, unjustly accused, sentenced, and condemned to death, he does not cry out curses and abuse on his tormentors, as do the dying “lestai.” Instead, he forgives them. He dies with love on his lips, not hate. He didn’t sell his life for cheap, but spent his life expensively, extravagantly, for the benefit of the world. His death advances an eternal cause—it is death that leads to life. He called disciples who would share that life, that vision with him, even if it led them to their own cross. They would not die seeing the end of hope, but as Jesus’ resurrection from the dead proved—it was only the beginning of God’s kingdom. He’s still calling us to follow him in the way of the cross. He died in our place so that we might live—not so that we can throw away our lives on cheap, imitation, warped visions of the future, but to spend them wisely, extravagantly, on his very own mission and vision of a world free from sin and death.

We don’t know what happened to Barabbas after he was released. Some optimistic old legends say that he became a follower of Jesus, realizing that Jesus had died for him, and that later he himself was martyred, but this time for the cause of Christ and his kingdom. That would be a great story and some recent movies have tried to portray him that way (though the actor who played Barabbas in The Passion of the Christ did indeed convert to Christianity as the result of his experience of playing the one whom Jesus died for). Had that happened, however, we might have expected the writers of the New Testament to tell us about it. More likely, Barabbas saw his release as an opportunity to go back to his revolutionary work. If he was a young man when Jesus died in his place, then Barabbas may have been around long enough to see his revolution come to a head in 70AD when the zealots barricaded themselves in the temple, turning it into

We don’t know what happened to Barabbas after he was released. Some optimistic old legends say that he became a follower of Jesus, realizing that Jesus had died for him, and that later he himself was martyred, but this time for the cause of Christ and his kingdom. That would be a great story and some recent movies have tried to portray him that way (though the actor who played Barabbas in The Passion of the Christ did indeed convert to Christianity as the result of his experience of playing the one whom Jesus died for). Had that happened, however, we might have expected the writers of the New Testament to tell us about it. More likely, Barabbas saw his release as an opportunity to go back to his revolutionary work. If he was a young man when Jesus died in his place, then Barabbas may have been around long enough to see his revolution come to a head in 70AD when the zealots barricaded themselves in the temple, turning it into  a fortress like the Alamo, until the Romans broke through, killed or captured the defenders, and let the temple burn. After that, Jerusalem was ringed with the crosses of the zealots—so many that the Romans ran out of wood to build them. We might wonder if Barabbas met his end there and what he thought as he watched the temple, his hopes, his dreams, and his cause burn to the ground.

a fortress like the Alamo, until the Romans broke through, killed or captured the defenders, and let the temple burn. After that, Jerusalem was ringed with the crosses of the zealots—so many that the Romans ran out of wood to build them. We might wonder if Barabbas met his end there and what he thought as he watched the temple, his hopes, his dreams, and his cause burn to the ground.

Pilate stood up two Jesus’ in front of the crowd. Which one do you want? Jesus of Nazareth, or Jesus Barabbas? It’s the same choice offered to us today:

Will we follow the clamor of the crowd, choose the Jesus of the quick fix and give our lives to visions of temporary glory, even if it costs us our lives? Following the crowd, it seems, almost always leads to choosing the way of Barabbas.

Or will we pick up a cross and choose the Jesus who gave his life for the world? The Jesus who taught us to pray to his Father, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” is the same Jesus who then went out and acted as though that kingdom is already here. He is still gathering disciples and challenging them to give their lives to that cause—the cause of his kingdom.

Jesus Barabbas is dead. Jesus, Son of God, is risen from the dead. Which Jesus will you choose?