First in the series “Beginnings: The Story of Genesis.”

Genesis 1:1-2:3

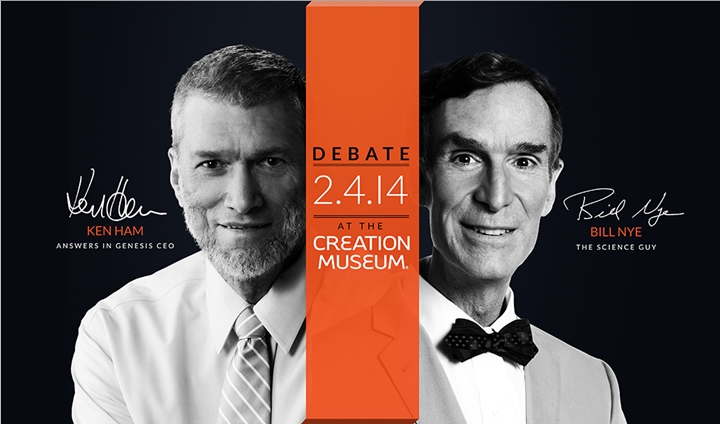

You may have seen this debate a few weeks ago between Bill Nye (The Science Guy) and Ken Ham the director of the Creation Museum in Kentucky concerning the origins of the universe. If you didn’t see it, as I didn’t, that’s ok—debates like this have been going on for decades, even in traffic. All you need to do is drive around and you’ll see Christian fishes vs. Darwin fishes with legs.

You may have seen this debate a few weeks ago between Bill Nye (The Science Guy) and Ken Ham the director of the Creation Museum in Kentucky concerning the origins of the universe. If you didn’t see it, as I didn’t, that’s ok—debates like this have been going on for decades, even in traffic. All you need to do is drive around and you’ll see Christian fishes vs. Darwin fishes with legs.

And the root of this debate actually comes back to the Bible and the story we’re going to be looking at over the next several weeks. The book of Genesis offers us a story, as many Christians would claim, on how the world came to be. Science, of course, claims to offer a different understanding of how the world came to be. The conflict, as many people see it, is between the natural and the supernatural, the empirical vs. the certainty of faith.

There’s a lot at stake in this debate for many people. I’ve been in college classes where secular university professors have railed against anyone who holds a biblical worldview, while I’ve also talked to scientists who have struggled to be in churches where their profession is discounted as being a deception from the devil. Many people wonder if they have to check their brains at the door when they come to church, or check their faith at the door when they go to class or to their workplace. Many Christians are afraid that if the accounts of creation didn’t happen exactly how and when the Bible seems to say that it does then the rest of the Bible must not be true, either, while many scientists struggle to hold their faith in tension with the evidence of fossils and geologic time.

But is this debate really necessary? Is science vs. faith a false dichotomy and is there a way to reconcile the two together. Or, better yet, is there a third way—a way of understanding creation and the stories in Genesis that allows the text to be authoritative while, at the same time, making room for the discoveries we make and observe in the world every day? It’s clear that debate isn’t the proper forum for that discussion (actually, it’s not a discussion—more like lobbing salient points back and forth). The only way we can answer those questions is by going to the text itself and seeing it within the context of the larger story. I want to suggest that as we study Genesis over the next several weeks, we will see that the biblical text is actually much richer than we imagined, the story much more compelling. Rather than a flat science text book or a mythological flight of fancy, Genesis is actually a very sophisticated piece of literature and revelation from God that speaks to issues far deeper than the likes of Ken Ham and Bill Nye could ever debate. In the main, Genesis isn’t a story about rocks, dinosaur bones, and big bangs—it’s the story of God and the story of us.

To study Genesis is to explore what it means when we say that the Bible has “authority.” That word “authority carries a lot of freight in the Bible. When Jesus commissions his disciples at the end of the Matthew 28, he begins with “All authority in heaven and earth has been given to me” (and, the implication, “now I give it to you.”). God’s purposes will be carried out through humans, which is really the basic plot of the whole Bible. We see time and again how God chooses people to accomplish his purposes, usually the most unlikely people—God’s authority is vested in them. And this is true of the biblical writers themselves. For whatever reason, God chooses human authors to convey his purposes—his authority is vested in them, his word breathed to them, as Paul says in 1 Timothy—and their words are the way we get to understand God’s purposes, insofar as human language can convey them.

To study Genesis is to explore what it means when we say that the Bible has “authority.” That word “authority carries a lot of freight in the Bible. When Jesus commissions his disciples at the end of the Matthew 28, he begins with “All authority in heaven and earth has been given to me” (and, the implication, “now I give it to you.”). God’s purposes will be carried out through humans, which is really the basic plot of the whole Bible. We see time and again how God chooses people to accomplish his purposes, usually the most unlikely people—God’s authority is vested in them. And this is true of the biblical writers themselves. For whatever reason, God chooses human authors to convey his purposes—his authority is vested in them, his word breathed to them, as Paul says in 1 Timothy—and their words are the way we get to understand God’s purposes, insofar as human language can convey them.

But once we understand that God’s purposes are revealed through human agents and human authors, we then have to confront the reality that those authors are set in a particular time and place in history. They are writing to a specific people in a specific language in a particular culture. While Scripture is certainly written for us, it was not originally written to us. It was not written in our language, it doesn’t use our cultural reference points, our idioms, nor does it have our 21st century worldview. One of the most interesting books I’ve read recently is Misreading Scripture Through Western Eyes by Randy Richards and Brandon O’Brien, who say, “We can easily forget that Scripture is like a foreign land and that reading the Bible is a crosscultural experience. To open the Word of God is to step into a strange world where things are very unlike our own.” In order to understand what the text is saying to us, we have to first try and understand what it meant to the original author and to the first people who cracked open the scroll. When we do that, when we see the world the way the text sees the world, then we can begin to understand what it might mean for us and the way we understand the world. The message of Scripture transcends culture, which is why we’re still reading it and hearing God’s purposes in the 21st century, but the text is also culturally bound.

This is one of the reasons why the controversy over the text of Genesis 1 is so misguided. When Ken Ham and Bill Nye the Science guy engaged in their debate over the merits of creationism vs. evolution, they both missed the point because neither of them considered the biblical text in its context and through the worldview of ancient Israel. They were using scientific categories that ancient people would not have even considered.

Take this picture, for example. You know what this is. We know that the world is a globe, that it revolves around the sun, that’s part of a solar system. We know that planets and stars are material objects, that the universe is expanding, that the moon we look at in the night is actually a giant grey rock orbiting the earth. Show this picture to an ancient Israelite, however, and they would not have known what you were showing them. Their understanding of cosmic geography was quite different.

Take this picture, for example. You know what this is. We know that the world is a globe, that it revolves around the sun, that’s part of a solar system. We know that planets and stars are material objects, that the universe is expanding, that the moon we look at in the night is actually a giant grey rock orbiting the earth. Show this picture to an ancient Israelite, however, and they would not have known what you were showing them. Their understanding of cosmic geography was quite different.

Looking at the Genesis text, we see that the Israelites believed that the earth was essentially flat, set up on pillars, with a fixed dome over it separating “the waters above” from the “waters below.” The moon and sun were lesser and greater “lights” not objects in the vastness of space. The “deep” surrounded the pillars under the earth and that’s where the great creature the leviathan lived. This wasn’t just an Israelite view, most ancient peoples had a similar understanding of cosmic geography, with variations on which gods and goddesses controlled the various parts of the cosmos. The big difference with Genesis, however, is that only one God creates and controls the whole thing. But Genesis has much more in common with the cosmology of their ancient neighbors than it does with ours. God is not offering them a new understanding of the world and the universe, he is working with the one they have.

In fact, if we look back at history, we see that the human understanding of cosmic geography is always changing. In the 16th century, Copernicus posited that the earth actually revolved around the sun, not the other way around which was thought for centuries. More recently, most of us grew up believing that there were 9 planets in our solar system, until a few years ago when Pluto was declared to no longer be a planet (scientists discovered that there wasn’t just one planetary-type body at the edge of the solar system, but about 300—so they either had to include all 300, making it hard for school children to memorize, or cut out Pluto). The point is that God works with people where they are in time and place. Genesis is not a scientific account because the author and the readers didn’t know anything about science. They didn’t use their brains to think about it because, well, they didn’t even know that the brain was the center of thought (the word for “mind” in Hebrew is the same as “entrails.” There is no word for “brain” in Hebrew. In other words, they were literally thinking with their guts.).

So, what does Genesis 1 actually tell us about God? About the world? About humanity? What does the text mean when it says that God “created?” To get to the guts of the matter, we have to suspend our 21st century, post-Enlightenment categories and consider what the text actually says. John Walton, professor of Old Testament at Wheaton College, has written a fascinating book called The Lost World of Genesis One that looks in depth at the Hebrew text in its context and has come to the conclusion that Genesis 1 is not describing the material origins of the universe, as we have commonly understood it in our scientific age, but rather what the text reveals to us is the functional origins of the world. In other words, Genesis is less about how God made the world than about how God made it to function.

Look at how the text begins: “In the beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the waters.” It’s interesting that when we read this familiar text we miss the fact that God is starting his creation with raw materials. If this was a text concerned with material origins (i.e. the Big Bang Theory), we would expect the text to start with nothing. But here we have this formless void, darkness, and “the deep.” We miss this, but an ancient person would have understood what’s going on here. These are all indicators of chaos and non-order. The Hebrew word for “formless” is tohu—it means to lack worth or purpose.

And what is God’s response to this non-order? He “creates.” The Hebrew word for “create” is bara. When we think of that word “create” we normally think of it as forming matter, right? We “create” a piece of art, a building, etc. But we can also “create” a committee, a curriculum, a piece of music. “Create” can refer to a lot of things, so to understand what we mean when we see that, we have to look at the way the writer tends to use it. In the case of bara it is used some 50 times throughout the Old Testament and in most of those usages, the direct object of the verb has to do with creating something for a specific role or function. God doesn’t just create a material thing, he creates it for a specific purpose.

Look at the first day of creation—God says “let there be light.” Now, we know now from science that light is actually an object, and if God was focusing on material origins here we would expect God to call the light, “light.” But look at what the text says (verse 5): “God called the light ‘Day’ and the darkness he called ‘Night.’” What is God actually creating here? Not merely the object of “light” but rather the function of time! Day and night, evening and morning—light separated from the darkness. And notice what God calls this light: “God saw that the light was good.” What does “good” mean in this context? It means that the light is functioning properly, as designed.

Day 2, God “separates the waters above from the waters below. The waters “above the dome” are where the ancient Hebrews believed the rains came from. What is God creating here? The function of weather.

Then Day 3. God separates the land from the waters (order from chaos) and then (v. 11), God says “Let the earth put forth vegetation: plants yielding seed and fruit trees of every kind…” Is God creating vegetation here? Yes, but what’s it’s function? Bringing forth food. Time, weather, and food—all things that are necessary for human existence (and the things we tend to talk about and be concerned with the most!). These are the basic functions of the created order.

Days 4, 5, and 6 then are about God installing the functionaries who will operate within the spheres of these three functions. Notice that on days 4-6 the description continues to be functional (notice on day 4: signs, festivals, days and years—all functional in relation to people). Notice, too, that on Day 4 God creates the greater and lesser lights that we know as the sun and moon. It seems strange that sun and moon only appear in Day 4, after God has created light. You would have to do a lot of scientific and exegetical gymnastics in order for that to make any sense in our understanding. But the contradiction only exists if this is an account of material origins. In a functional perspective, time is much more significant than the sun; the former is a function, the latter simply a functionary. Day 5 is the creation of animals, whose function is to “be fruitful and multiply” and fill the earth. And then, Day 6, is the creation of humankind, whose function is to care for the creation, have “dominion” over it, and reflect the image of God within it. Everything is created for a purpose, and at the end of the sixth day, God looks at it all and calls it “very good”—it is all functioning as he intended.

But then there is this curious description of the seventh day: “And on the seventh day, God finished the work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all the work he had done. So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work he had done in creation” (2:2-3). This is a curious text that many debaters actually skip completely—What does God need to rest? God is after all a Spirit, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. Why does he need a nap after all this? And what does this resting have to do with creation?

Well, actually, this description of the seventh day is actually the key to understanding all of Genesis 1 and, indeed, the whole biblical narrative. We don’t see it, but ancient people who were reading this text would instantly understood what it was: this is a Temple story. In the ancient world, in every culture, people believed that gods only “rested” in temples—indeed temples are constructed for this purpose. And temples were not merely residences for the gods, they were the places from which the gods controlled the cosmos.

All of this is bound up in the word “rest.” When a god is at rest, that means that there is security and stability within an ordered system because that god is in control. This is not rest in the sense of relaxation, but rest in the sense of engagement, rule, and order. In the Genesis narrative, different from the other pagan cultures of the Ancient Near East, there is one God who “rests” and reading this text those ancient Hebrews would have known that this was the point of the first six days of creation, of God setting things in their proper order and function: It was now prepared as a temple in which God would dwell with his people. The seventh day, in other words, is an Emmanuel moment—it is the moment when God moves in to his creation—the moment he comes to dwell with us! The first six days are really about God building a house. The seventh day, it becomes a home.

The parallels through the rest of Scripture are unmistakeable when we see them through this lens. When the Shekinah glory of God descends on the tabernacle and temple, it is said to “rest” there. Psalm 132 says, “Rise up, O Lord, and go to your resting place, you and the ark of your might…For the Lord has chosen Zion; he has desired it for his habitation. ‘This is my resting place forever; here I will reside, for I have desired it.’” Jesus says, “Come to me all you who are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” “Rest” means that God is with us and everything is “very good.”

This is really the point of the creation story: God at rest, dwelling with his people. The creation is not merely a collection of material things that were scientifically or supernaturally formed—the creation is the place where God dwells with his people. God dwelt with the first humans in a Garden, he dwelt with Israel in tabernacle and temple; God became the “Word made flesh” that dwelt among us in Jesus Christ. And, at the end of the Bible, just like at the beginning, the main point is God dwelling with his people again. Revelation 21:1-3: “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more [chaos eliminated]. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem [the dwelling place of God] coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying: ‘See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them;’”

This is the glory of the creation story. It’s not so much about the how but about the who. It’s a text that calls us not to scientific speculation but to Sabbath. It’s a call for us to cease from making our own order out of the world for one day and to remember that it is God who brings order. This is why God gives the command to the Israelites to “remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy [set apart, dedicated to God]…For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all this is in them, but rested on the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the seventh day and consecrated it” (Exodus 20:8-11). This is the day we cease from our dysfunction and we remember to function in the way for which God created.

Debating how old the earth is was never the point. Regarding how things got here or how long it took, the message of Genesis is pretty simple: God did it. The real question Genesis wants to answer is for what purpose God did it. And the answer to that, according to Genesis 1, is equally simple: he did it in order to dwell with us.

Truth is, we need a lot less debate and a lot more Sabbath, a lot less wrangling over material origins and a lot more worship. That’s what we gather here for on Sunday morning, a Sabbath day. We gather to stop our daily routine, our attempts at controlling the world around us, and we simply worship. We enjoy God’s dwelling with us. We gather at the table with Christ, God with us. We are reminded again, as the prophet Habbakuk reminded Israel, that “God is in his holy temple; let all earth keep silence before him” (2:20). We gather to hear the promise of Scripture, that God will rest with us forever. Where creation has been gives way to where it is headed—to the glory of God who makes all things new.

So, let science do its work and celebrate the mysteries of the cosmos as a gift from God. But also, let the text do its work in us. This is God’s world and he dwells with us. That is better news than any debate could ever manufacture!

Note:

For a video of John Walton describing this view of Genesis, click here.