I returned on Sunday afternoon from the Rocky Mountain UM Annual Conference session in Pueblo and after a few days of rest and reflection (some necessitated by an intestinal virus I picked up while there), I’ve been pondering the question the Bishop posed in her Episcopal Address—namely, given the deep divisions in the church right now over homosexuality and other issues, “Where do we go from here?”

I am one of a small minority of colleagues in the Rocky Mountain Conference who are theologically orthodox and who believe that the Discipline’s current language on the particular issue of human sexuality accurately reflects the biblical witness and the history of the church’s thinking on the matter. I respect that others disagree with me on this issue (and many others), and yet we have remained friends since I entered the conference in 1998. I learned a lot about being an ecclesiastical minority while serving for seven years in Utah, where Protestant Christians are heavily outnumbered by their LDS neighbors and yet I gained some great friends from among those with whom I have little in common theologically. Those lessons are still instructive to me in the current unrest and calls for schism in the United Methodist Church.

The tension at annual conference this year was palpable, even though we focused much of our energy on remembering the Methodist Church’s role in the Sand Creek Massacre 150 years ago. That seemed appropriate to me, and the visit to the site was powerful. It was good to focus on something on which we could all agree. Still, everyone there was aware that as we move toward next year’s conference, where we will elect delegates to the 2016 General Conference and no doubt address a myriad of petitions on human sexuality and other divisive issues, things have the potential to get ugly. It’s tough to be in a small minority when that’s the case.

Some of my conservative colleagues in the UMC have proposed “separation” as a solution to the divide—that one way to stop fighting is to simply go our separate ways and believe and practice as we wish. I listened in on a couple of those conference calls in order to understand the rationale and the potential plan. Others have proposed compromises, like one put forth by some pastors of our largest churches that would in effect allow conferences and congregations to choose how they are going to operate—“unity” in the guise of doing our own thing. That seems to me a congregationalist approach and not a Wesleyan solution to the problem. Every day it seems someone is coming up with one plan or another for keeping us together or keeping us apart.

Before conference, I read the new edition of Howard Snyder’s The Radical Wesley which was recently published by Seedbed. Snyder offers a unique look at the way in which Wesley approached leading the Methodist movement within the Church of England without ever separating from it. It wasn’t until after his death that the Methodists became a separate church. Wesley was a Church of England clergyman his entire life and even though he led a small holiness movement that was never blessed by the Church and wound up being banned from most Church pulpits, he never allowed the movement to become detached. Wesley had deep disagreements with the preaching, polity, and process of the Church, but he stayed anyway and kept the Methodist movement connected in spite of the differences.

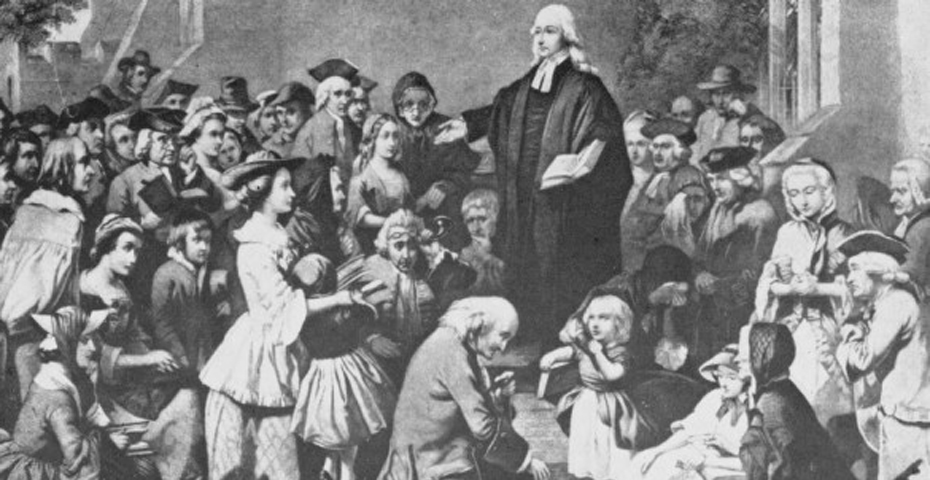

Wesley’s example struck me as one option that few who have been wrangling over the future of the United Methodist Church have explored—that of a specific, focused movement from within the institution. The options for schism on the one hand and unity on the other seem to assume that we have to continue doing church in the way we’ve always done it and thus it’s a matter of buildings and pensions and appointments. Wesley, however, chose a completely different option: he took the movement outside. Where he once “thought the saving of souls almost a sin if it had not been done in a church,” when the situation required it he “submitted to be more vile” and took to preaching in the fields and, in one famous case, even on his father’s tomb when he was refused the opportunity to speak in the pulpit of the church in which he grew up. Oh that we could take all the energy we’ve been spending trying to keep things in line within the Church and channel it into being so vile!

And yet, while the movement went outside, it never departed from the established Church. I did some searching and discovered that in 1758, John wrote a piece in Charles Wesley’s larger volume Hymns for the Preachers Among the Methodists (so called) in which he reminded those preachers of the reasons why the Methodists should continue to stay connected to the Church of England. The proposal was entitled, Reasons Against a Separation from the Church of England and in it John Wesley laid out twelve reasons why the Methodists would not promote schism in spite of the Church’s apostasy and its antagonism of the Methodist movement. Many people have evoked Wesley’s sermon on Catholic Spirit (often out of context) as a case for “unity.” What Wesley actually says in Reasons Against a Separation, however, strikes me as a clearer and more powerful argument for staying connected while never wavering from the task of spreading scriptural holiness throughout the land—an argument that seems prophetically aimed at those of us who increasingly find ourselves on the outs with the denomination and its direction.

In the posts that follow I will take Wesley’s twelve propositions point by point and offer some commentary on what I think they might mean for us going forward. Indeed, this might be the beginning of the road map that actually offers an answer, at least for some of us, to the question, “Where do we go from here?”